Historic Sites as Classrooms: On-site Teaching of Cultural Heritage Education

How can cultural heritage transcend being a specimen for one-time viewing and be integrated progressively into contemporary daily life? The general Taiwanese experience of early historic sites is limited to cursory guided tours, with the buildings themselves seeming frozen in time, disconnected from urban life. Addressing this, Professor Jung Fang-chieh proposes a solution using ‘curatorial thinking’ to showcase multiple dimensions of historic sites, and implements this philosophy through lesson planning, bridging the gap between old buildings and people starting from basic education.

For the finale of the ‘Good City Talks’ cultural heritage promotion lecture series, we invited Professor Jung Fang-chieh from the Department of Environmental and Cultural Resources at National Tsing Hua University to the old house café and bookstore ‘Bookstore Café 123 Pavilion’ to speak on ‘Historic Sites as Classrooms: On-site Teaching of Cultural Heritage Education.’ He discussed the importance of interpreting cultural heritage in the digital age and explored diverse presentation methods from domestic and international cases, envisioning sustainable directions for preservation and promotion of local cultural heritage, and relevant on-site education.

Historical Interpretation Beyond Frameworks

“The purpose of preserving cultural heritage is to understand how we became who we are today.” Professor Jung Fang-Chieh begins with this statement, explaining that the cultural value of old buildings lies in their cross-generational spatial narrative. Therefore, beyond the repair and maintenance of physical structures, the question how to guide the public to observe both the macroscopic urban development and microscopic changes in daily life, thereby tracing one’s own position in the flow of time, is a crucial issue in Taiwan’s current efforts toward preservation of its rich cultural heritage. However, the temporal sequences displayed in most historical sites remain fragmented, and often present spatial artifacts through a single perspective, without offering opportunities for repeated viewing.

Take Fort Zeelandia in Tainan as an example. This fortress, initially built in 1624, has witnessed the transitions of power from the Dutch East India Company, the Zheng dynasty, the Qing Empire, and the Taiwan Governor-General’s Office, to the Nationalist Government. Although it has been registered as cultural heritage and opened to the public, its exhibition content still focuses on relics of commercial trade during the Dutch colonial period and the military aspects of the Zheng period. This is not only inadequate to outline the building’s four-century historical trajectory but also barely touches on the lives of the Dutch on this land. Professor Jung suggested that if Fort Zeelandia’s chronological changes were presented according to different historical periods, it might better demonstrate the concrete impacts these historical phases left on Tainan.

In contrast, the English Heritage Trust launched an ingenious drawing competition on Children’s Day in 2016. They translated important events in the development of Britain, such as the Norman Conquest of England, the signing of the Magna Carta, the Black Death pandemic, and the outbreak of the Wars of the Roses, into a series of colorful tapestry designs. They then invited children to depict contemporary society, leaving annotations for their era. This approach echoes Professor Jung’s view—only after clearly recognizing historical contexts can people understand “how they became who they are today,” and thereby appreciate the value of history and the close connection between ancient and modern life.

One Hundred Perspectives on Viewing Cultural Heritage

In the internet age where information is relatively and widely easy to access, the public’s need for museums is no longer simply a quest for knowledge; rather, they need content value presented according to exhibition themes after selection and organization. The same applies to the preservation and presentation of cultural heritage. Historical spaces that have accommodated human activities through eras possess rich trajectories of change, which can be transformed into diverse expressions through the ingenuity of curators both domestically and internationally.

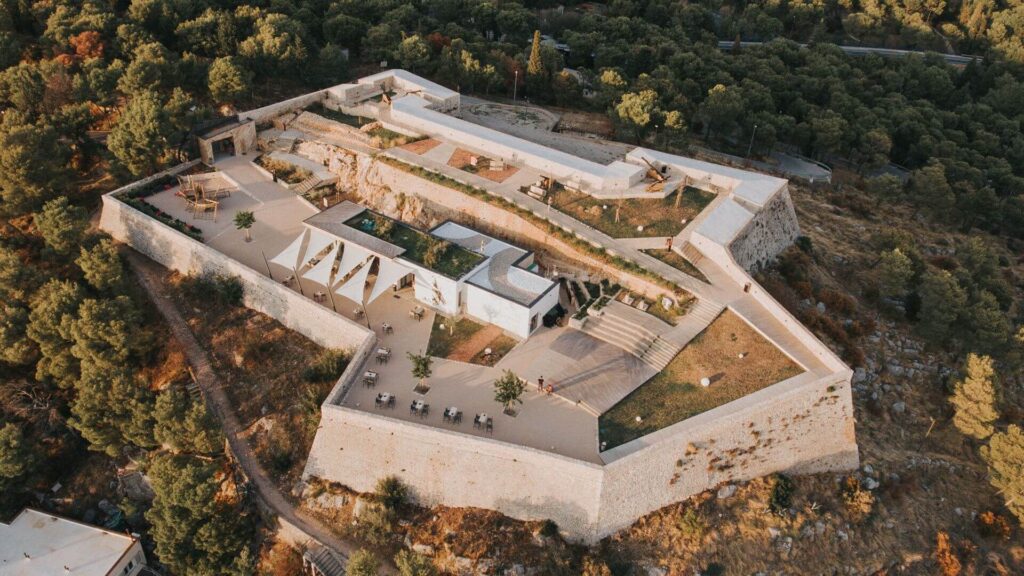

Consider Croatia’s Šibenik ‘Barone Fortress’ as an example. This historical site with most of its structures damaged now uses Augmented Reality (AR) devices to guide visitors through a 3D simulated restored landscape. Besides recreating the naval battle with the Ottoman Empire in 1647, the program also presents the changing appearance of the fortress throughout different eras along the guided route. The local government of Šibenik, responsible for managing four ancient military fortresses, operates these historical sites from a macro perspective of ‘city governance,’ assigning different core themes to each fortress to showcase the region’s rich and diverse cultural foundation.

Portugal’s ‘São Jorge Castle Archaeological Site Museum’ in Lisbon takes a ‘spatial design’ approach, building new lightweight white structures based on reversibility principles on top of the prehistoric ruins of which only broken walls remain. This design allows people who have never encountered archaeological remains to enter the historical site, experience the concrete spatial dimensions, and delve into an imaginative journey into early life.

Another example is the ‘Benjamin Franklin House’ in London, England. This utterly ordinary-looking terraced house is the only surviving residence of Benjamin Franklin. Rather than filling the space with artifacts and furniture, the management team uses unique ‘theatrical performances’ to showcase the last day spent there by the American Enlightenment pioneer. An actress playing Polly, the landlady’s daughter and Franklin’s close friend, serves as a guide, interacting with sound and light props in each room to lead visitors into a small London apartment in late spring 1775, allowing them to experience the vibrant historical atmosphere of the era through live performance.

In 2010, to celebrate Chopin’s 200th birthday, Warsaw, Poland installed specially designed benches at 15 locations (mostly historic palaces, churches, and parks) where the great composer had performed, met people, and lived. The bench surfaces present maps showing the distribution of all ‘Chopin Benches’ in the district and also feature built-in audio devices that play piano music of Chopin’s works when pedestrians press the play button. These pieces of ‘street furniture’ not only connect historical sites through a common theme and explore the cultural value of old buildings from multiple perspectives, but also successfully integrate exhibits into contemporary daily life, allowing more people to experience the historical atmosphere surrounding Chopin and his era.

Entering the Fundamental Education of Cultural Heritage

Since the 2016 amendment to the Cultural Heritage Preservation Act, collaboration between cultural and educational departments has become a trend, yet the long-standing gap between these divisions remains difficult to bridge—the examination-oriented education system that emphasizes textbook knowledge seems to contradict the concept of ‘leaving the classroom and entering cultural heritage sites.’ Regarding this, Professor Jung Fang-chieh points out that past introductions to historic buildings have mostly focused on historical disciplines while overlooking the interdisciplinary wisdom inherent to these structures: we can learn concepts of physics from building structures, apply mathematics to calculate courtyard areas, understand chemistry from the materials used in wall paintings and pigments, and even study language applications through calligraphy and couplets. In other words, cultural heritage can be integrated into teaching contexts in various forms.

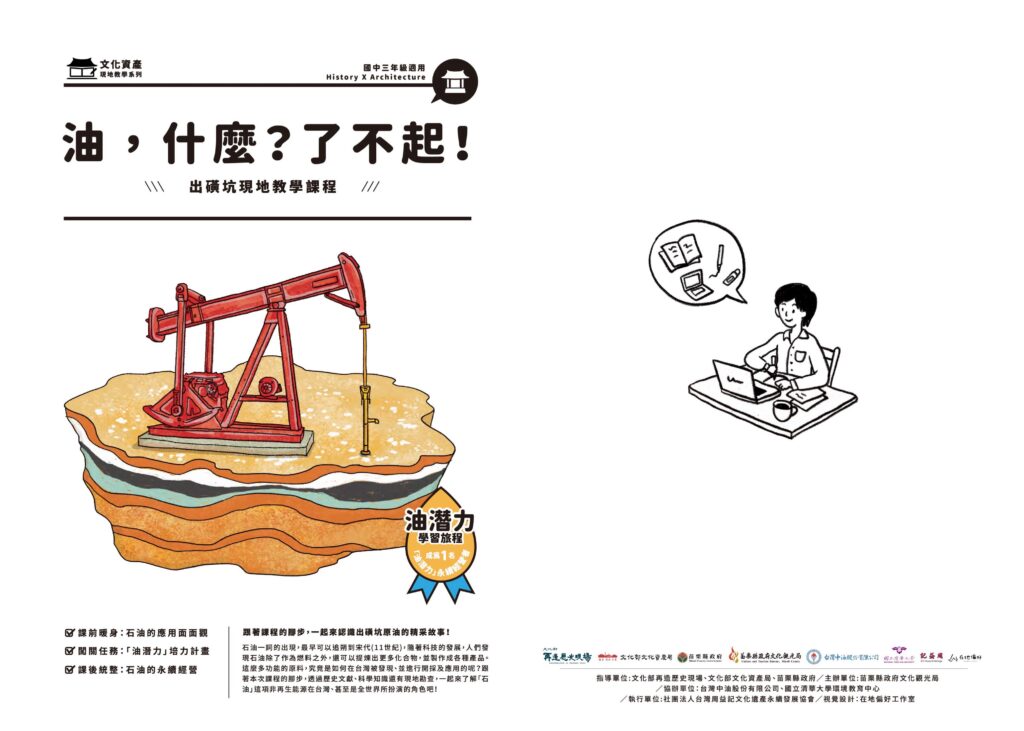

Taking the ‘Miaoli Chuhuangkeng’ on-site teaching curriculum previously designed by Professor Jung Fang-chieh and his team as an example, a careful examination of the development process of this oil mining industrial heritage site can unravel rich knowledge spanning history, geography, settlements, and industries. Starting from the primary and secondary school curriculum framework, they extended opportunities for more in-depth and concrete subject application. This ‘Entering Historical Sites’ on-site teaching curriculum not only extends cultural heritage new opportunities for revival but also allows students to personally witness the practical application of interdisciplinary knowledge, broadening their perspectives on diverse career paths beyond the examination system.

Additionally, Professor Jung Fang-chieh mentioned that if children can approach and use cultural heritage spaces in ways that interest them from an early age, visiting historic sites will become a natural habit, expanding profound humanistic literacy through repeated exposure. Thus, ‘cultural heritage’ will no longer be synonymous with dullness, but rather become the foundation for building deep connections between oneself, one’s hometown, and culture—this approach shares the same principle as the aforementioned ‘curatorial thinking,’ both interpreting and designing cultural content to showcase the rich connotations and contemporary significance of cultural heritage.

‘Historic sites are our classrooms.’ This is the slogan Professor Jung Fang-chieh established for education on cultural heritage, and also one of the future directions for promoting historical spaces in Taiwan. It is hoped that through collaboration and connection among interdisciplinary professionals, old buildings can be transformed into learning venues for diverse themes, strengthening different generations’ sense of identity with local spaces and enthusiasm for exploring historical and cultural contexts, further promoting the sustainable regeneration of cultural heritage.