A Century-Old Station Building Preserving the Glory of an Era:

A Trip Journal to Tokyo Station Hotel

Since its opening in 1914, Tokyo’s Marunouchi Station Building has been a vital transportation hub. It has also served as a cornerstone of the Marunouchi district’s regeneration, working with surrounding buildings to create an urban fabric where old and new coexist. Nestled within this historic structure, the Tokyo Station Hotel, established in 1915, is far more than just a railway hotel. It is a unique venue that allows guests to step directly into history and experience the atmosphere of a bygone era.

This unique fusion of heritage and modernity is what inspired the X-Basic Planning team to treat their stay as a form of pilgrimage while attending a symposium in Japan. As advocates for revitalizing old houses in Taiwan, they came not only to learn the station’s stories but also to see how a century-old building remains so vibrant and essential today.

A Symbol of Power Across the Oceans

From the bustling plaza, looking up at the Marunouchi Station Building, one sees Mikage stone (granite) decorative bands weaving between arched doorways, window lintels, and wall corners across the brick-faced facade. In the distance, the north and south towers gaze at each other, embodying the urban architectural style that flourished from the Meiji to Taisho periods. This decorative style, derived from the British Queen Anne movement, was pioneered by the master of modern Japanese architecture, Kingō Tatsuno. The magnificent Tokyo Station before us stands as the most representative work of his career. “Tatsuno-style architecture” not only became a defining feature in the evolution of Japanese architecture but also spread across the empire through the work of his numerous disciples.

If Tokyo Station is viewed as the intersection of Japanese modern architecture and railway history, then Taiwan’s public buildings from the same period reflect the parallel modernization experiments conducted under Japanese colonial governance. This distinctive style of red brick adorned with white bands and domed towers is evident in many Taisho-era government buildings, including the Presidential Office Building, the Control Yuan, the National Museum of Taiwan Literature, the National Hsinchu Living Arts Center, and Taichung Prefectural Hall. Beyond their functions as public spaces and political centers, these buildings—through their shared design language—projected the aesthetic ideals and governing authority the colonial administration sought to assert. In brick and stone, they constructed the imperial coordinates of an era onto the very land they occupied.

From Imperial Capital Gateway to Cultural Landmark

Building on this historical context, the Marunouchi Station Building in Tokyo’s heart was designed from the outset to carry a mission that transcended its role as a transport hub. At that time, despite the flourishing private railway systems, there was still a lack of a central hub that could integrate the complex network of routes—thus, the plan to build a ‘Central Station’ (renamed ‘Tokyo Station’ upon completion) was born. Given its special position as the capital’s gateway, the Japanese government invited renowned architect Tatsuno Kingo to design it. The station was designed not only to fulfill practical transportation needs but also to function as a national monument, a symbolic display of Japan’s rising power and its firmly established international status since the Meiji Restoration.

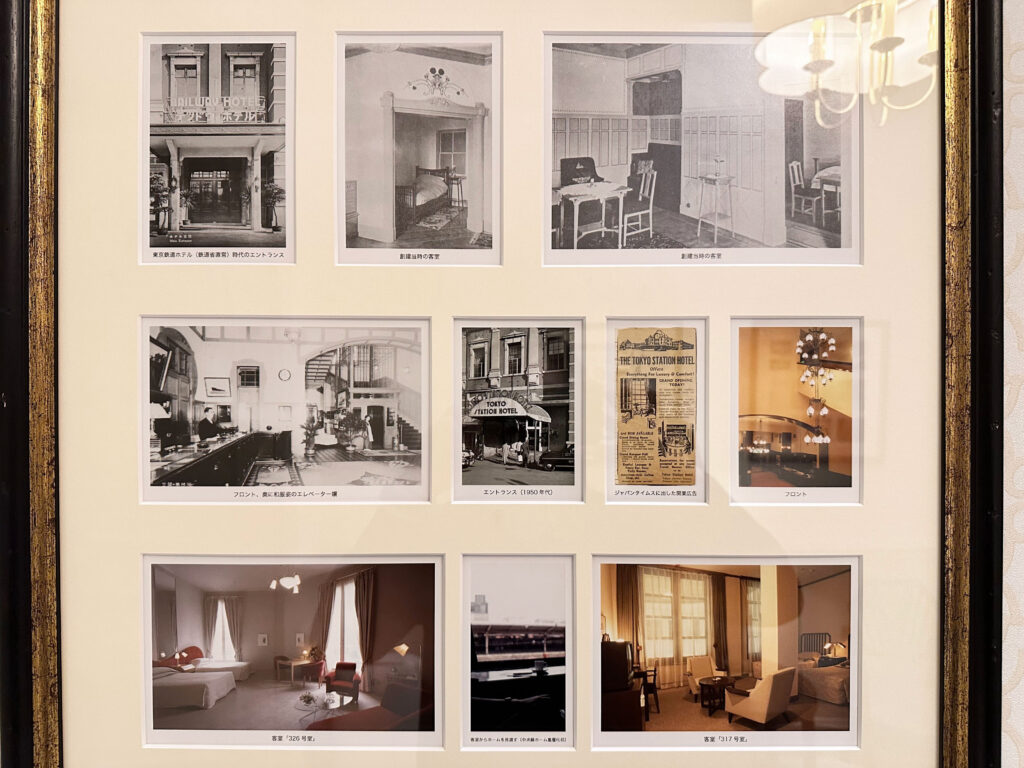

From its initial conception, the railway hotel was an integral part of the station building’s design. The Tokyo Station Hotel, which opened a year after the station’s inauguration, immediately established itself as one of East Asia’s most luxurious Western-style hotels. Thanks to its magnificent architecture, meticulous service, comprehensive modern amenities, and prime location directly adjacent to the station, it became a premier venue for hosting royalty, political and business leaders, and literary luminaries.

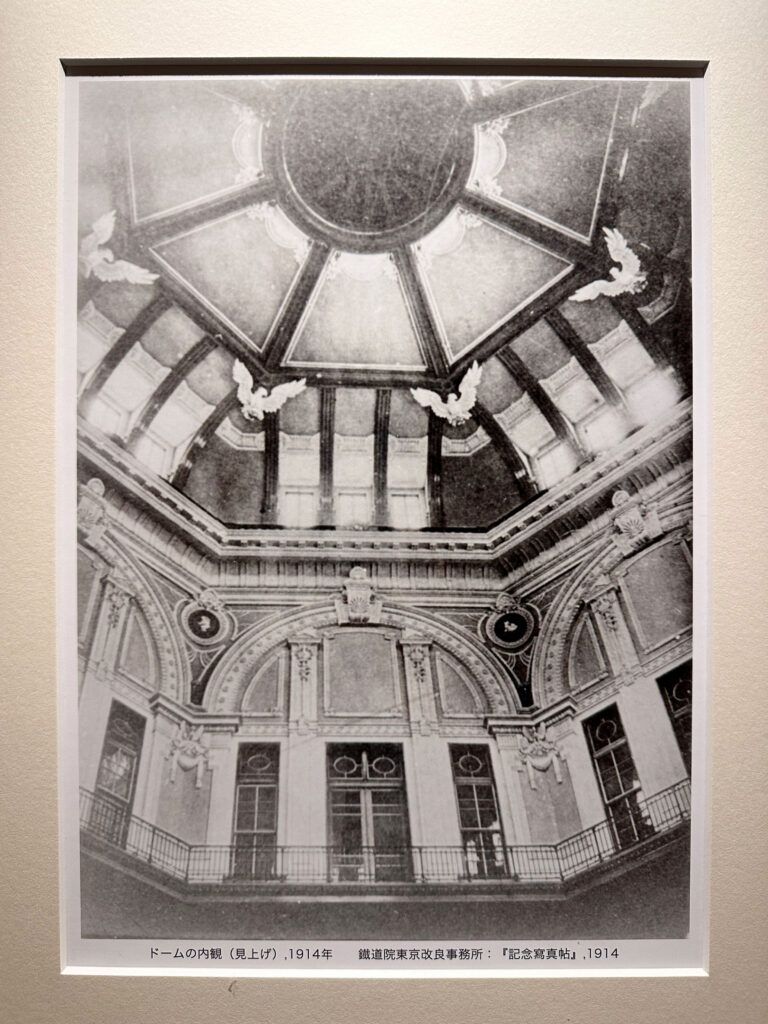

Figure 2: A historical photograph from 1914 showing the southern dome of the Marunouchi Station Building.

Figure 3: Interior of Tokyo Station Hotel, past and present comparison.

After its glorious beginning, this station, once a symbol of its era’s splendor, inevitably witnessed a century of turmoil. In 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake, a massive M7.9 event, struck the Tokyo metropolitan area. Its violent shaking toppled countless buildings, and subsequent fires ravaged the city, resulting in widespread loss of life. Remarkably, the Marunouchi Station Building, thanks to its resilient steel-reinforced brick structure, emerged from the disaster with only minor damage. It was swiftly transformed into a vital shelter for evacuees and supplies, becoming a symbol of hope for Tokyo’s reconstruction.

Even so, U.S. air raids during World War II brought devastating destruction—the incendiary bombs ignited fires that nearly consumed the slate roof and entire third floor of the station. The magnificent domes on both the north and south sides were left in ruins, and the hotel within was badly damaged, entering its longest closure since opening. Reconstruction began in 1947 under the constraints of a depressed post-war economy. The restored building was reduced from three stories to two, given a temporary sheet metal roof, and saw its bombed-out domes replaced with plain octagonal structures.

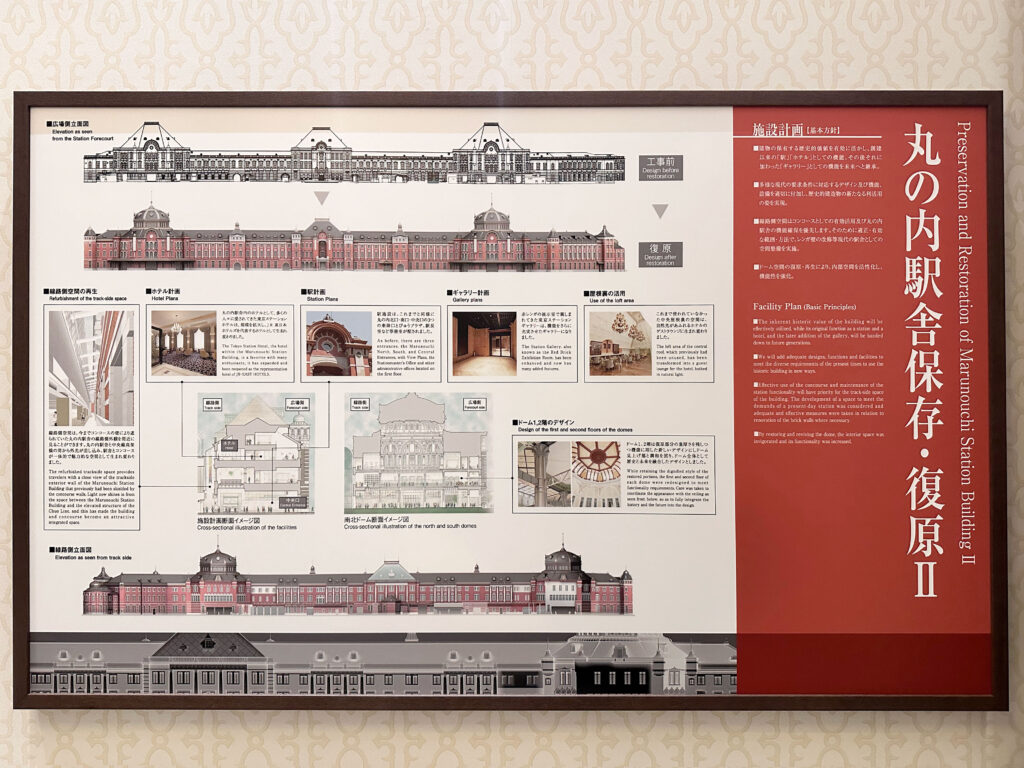

By the late 20th century, redevelopment plans in the Marunouchi district brought the fate of the old station into question. The management even proposed demolishing the building entirely and replacing it with a skyscraper, a plan that sparked strong opposition from local residents and preservation groups. This backlash led the government and related agencies to reevaluate the station’s cultural and historical significance, ultimately deciding to restore Tokyo Station to its original grandeur. In 2003, Tokyo Station was designated as an important national cultural heritage. The restoration project, undertaken in 2007, not only preserved and reinforced the original brickwork but also reconstructed the third floor and restored the elegant domes and clay decorative carving.

After six years of meticulous work, the Marunouchi Station Building was reborn in 2012. Its domes, absent for over half a century, was resurrected. The facade of red brick and white decorative bands radiated a warm glow, returning Kingo Tatsuno’s classic design to the public eye. Simultaneously restored, the Tokyo Station Hotel reopened with a new look, maintaining its status as a luxury hotel while weaving its century of history into the modern guest experience. It had transformed from an imperial gateway into a enduring cultural landmark.

As time moves through the railway stations.

The historical trajectory along Taiwan’s main railway line mirrors that of Marunouchi, yet the approach to preservation has differed greatly. Unlike Japan’s top-down restoration, awareness in Taiwan has advanced through a more challenging, bottom-up journey.

The 1986 replacement of the third-generation Taipei Station, driven by urban renewal and railway underground projects, ended an era and first galvanized public alarm over the vanishing railway scenery. The 1994 renovation of Hsinchu Railway Station, also built during the Japanese rule period, significantly altered its character by changing the roof from brick-red to light green. This act triggered the local government’s first preservation movement for the station, championing its significance as a consolidator of collective memories beyond its purely functional role.

The next year, a plan to relocate Taichung’s historic railway station was met with protests from the cultural community and railway advocates. They swiftly established the “Alliance for Promoting the Preservation and Regeneration of Taiwan’s Railway Stations” and organized a campaign that connected cities along the main line. Participants were called to depart by train from northern and southern Taiwan, meeting for exchanges in Hsinchu and Tainan before finally converging at Taichung Railway Station—a powerful demonstration of stations as essential public spaces. This action secured historic site status for old stations in cities like Hsinchu, Chiayi, and Tainan, ensuring their preservation and revitalization. It also established a framework for integrating railway heritage into urban renewal, culminating in Taichung Station’s unique feature of three generations of station buildings coexisting under one roof, where structures from different eras stand together and reflect the city’s historical depth. Despite ongoing challenges, these preservation movements succeeded in awakening widespread public interest in railway cultural heritage, demonstrating the significant impact of civic power on urban development.

From Tokyo Station’s turbulent life shaped by history to Taiwan’s railway architecture and its dialogue with modern society, the two places have followed very different paths of renewal: the former carefully restored as an Important Cultural Property, the latter driven by civic action and growing public awareness. Yet both reveal the enduring value of old stations as vessels of urban memory and local identity. For the X-Basic team, this journey was more than a pilgrimage; it was a chance to reflect on the cultural heritage preservation experiences of Taiwan and Japan. We aim to translate these insights into practical action, seeking new models of rebirth that fuse cultural heritage with sustainable operation, thereby empowering more historical sites that carry the stories of their communities.

Related Articles

【Island Brocade: Weaving a New Chapter in Global Heritage | Reflections from the Tomioka Silk Mill International Forum (11/1 Sat)】

【Following Historical Coordinates, Weaving a Cultural Heritage Regeneration Network | Notes from the Tomioka Silk Mill Study Visit】