Daily Life of a Master Craftsman: Architectural Craftsmanship and Artisans

“I’ve been a masonry master craftsman my whole life, and this is the first time someone has shown curiosity about this profession.” The 70-year-old Master Su Ching-liang responded with surprise during an interview, despite having already completed restoration projects for cultural heritage sites such as Taipei Public Hall and Hsinchu Prefecture Hall. This master craftsman, skilled in masonry and construction techniques, witnessed the transformation of Taiwan’s architectural industry through his lifetime. Although he passed away in 2023, the more than 30 revitalized old buildings he left behind, along with the ingenious craftsmanship they demonstrate, have already become important assets in the field of cultural heritage restoration.

In the ‘Good City Talks’ cultural heritage promotion lecture series co-organized by Kaohsiung City Cultural Bureau and X-Basic Planning, Professor Yeh Chun-lin from Department of Landscape Architecture, Chung Yuan Christian University was invited to the former National Women’s Association Hall, which was restored by master Su Ching-liang. Under the theme ‘Daily Life of a Master Craftsman: Architectural Craftsmanship and Artisans,’ he discussed the identity of ‘craftsmen’ who physically build architecture yet are rarely mentioned, reviewing the life of masonry master Su Ching-liang and the challenges of preserving traditional skills in contemporary society. He also engaged in a dialogue with Li Chih-shang, Chief Restoration Specialist from Mingxiang Culture, and Hsiao Ting-hsiung, Director of X-Basic Planning, to explore the diverse cultivation of Taiwanese craftsmen, their employment environment, and the current state of the cultural heritage restoration industry.

From Master Craftsman to Living National Treasure

The spirit of a city is embodied in its landscape. From the continuous arcade corridors along the streets, we can catch glimpses of the rainy climate, and from the carvings and murals of temples, we can understand local beliefs—these intricate architectural textures imbued with ancestral wisdom are carriers of intangible craftsmanship, and only through the generational transmission of traditional skills can cities continue to maintain their unique character.

After the war, as Taiwan’s economy developed rapidly, the mindset of ‘valuing principles over craftsmanship’ gradually took shape. The younger generation turned reluctant to inherit traditional crafts, and with buildings predominantly constructed using reinforced concrete, the decline of craftsmanship became an almost inevitable and regrettable trend. However, a single traditional Chinese house often encompasses six categories of craftsmanship: woodworking, stonework, brickwork, masonry (also called earthwork), painting, and cut-and-paste clay sculpture. From the beams and pillars supporting the entire space to the curved lines at wall junctions, every detail in the construction process relies on craftsmen performing their respective roles, applying techniques accumulated over years while coordinating with one another.

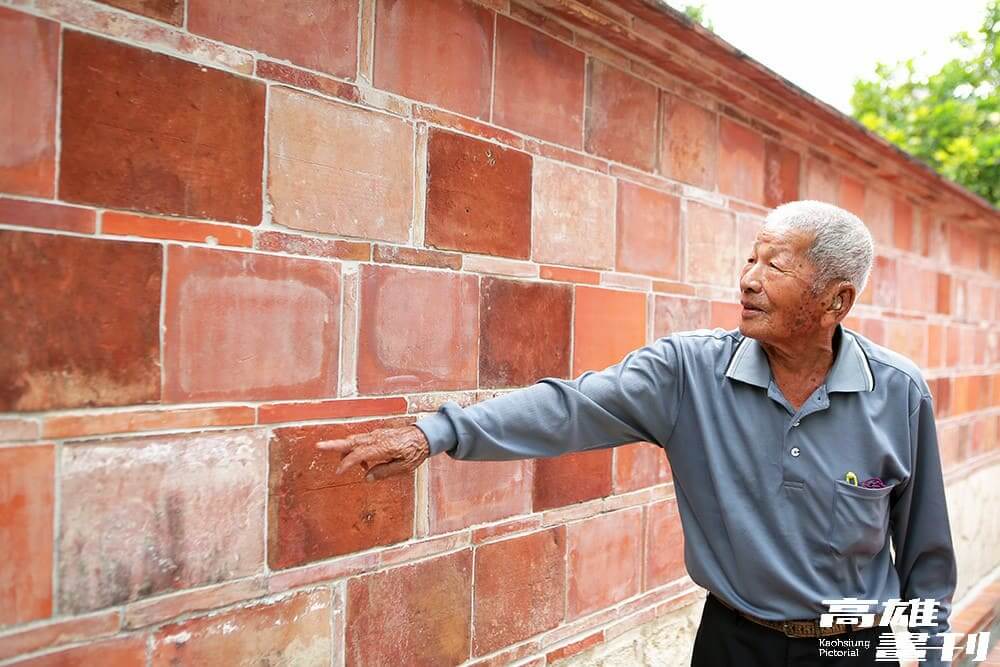

Professor Yeh Chun-lin noted that among the six traditional craftsmen, the ‘earthwork master’ responsible for leveling ground, laying bricks and tiles, and carving lime plaster lines had lower income and social status than others, yet played an indispensable role in shaping spatial atmosphere. Take Master Su Qingliang, who helped restore the lecture venue ‘Former Patriotic Women’s Association Hall,’ as an example. In his over 70-year career, he and his wife Su Hsieh-ying not only built numerous residential houses but also devoted their later years to the preservation of cultural heritage. After completing restoration projects for more than 30 historic monuments and buildings, he was honored as the ‘Preserver of Important Cultural Asset Preservation Technique in Earthwork Restoration Skills.’

Born in 1935, Su Ching-liang became an apprentice at 16 and, after three years and four months of apprenticeship, became an independent earthwork master. He started with traditional bamboo cage houses and rammed earth houses, then transitioned to undertaking masonry finishing work for townhouses after the war. In 1998, just as he was about to retire, he received an invitation from his son, who was serving as a site manager, to help restore the lime plaster lines of Taipei Public Auditorium (Zhongshan Hall). This marked his official entry into the prestigious field involving the restoration of historic monuments—from Fort San Domingo in Tamsui to Hengchun Ancient City in Pingtung, his restoration footprints can be found throughout Taiwan.

In this period, Master Su Ching-liang exchanged knowledge with Japanese plasterers including Shichiro Komatsu during the restoration of Taipei Guest House, and was astonished by the vast differences in tools used by craftsmen from both regions. For plastering trowels, Taiwan’s earthwork masters typically used stainless steel tools worth about 60 New Taiwan dollars, while Japanese trowels were forged from tungsten steel and produced by century-old craft brands specializing in trowels, costing over ten thousand yen. The difference in smoothness when applying plaster was immediately apparent between the two. Afterward, Master Su Ching-liang switched to tungsten steel trowels and even commissioned custom-made protective cases from carpenters. It was also through repeated documentation of construction and interviews with scholars (such as Professor Yeh Chun-lin) that he gradually recognized the value of traditional craftsmen and craftsmanship. He began recording his work: from tools used by masters during the Japanese colonial period and line templates individually made for each cultural asset over the years, to the intangible processes of masonry work—Master Su Ching-liang documented everything meticulously. In 2022, he was finally recognized by the Ministry of Culture as the preserver of the important cultural asset preservation technique in ‘earthwork restoration skills,’ and his profound craftsmanship continues to be passed down to younger generations after his grandson became his apprentice.

Entering the Craftsman’s Daily Life

Concluding, the speaker and two participants shared their insights on the preservation of traditional Taiwanese craftsmanship and restoration of cultural heritage. In contemporary society, where industrial structures and educational systems differ greatly from the past, the early model of skill transmission through family units or master-apprentice relationships has gradually declined. However, craft training programs transplanted to university education or government training often differ from actual practice. With younger generations rarely having close contact with old houses or craftsmen, how can traditional crafts continue to exist in the future?

Professor Yeh Chun-lin, drawing from his years of experience in university education, remarked that many architecture students initially aspire to build skyscrapers and modern buildings. However, after visiting old buildings on site and actually interacting with master craftsmen, they gradually recognize the value of traditional aesthetics and craftsmanship, incorporating these elements into their future creations and exerting a subtle influence on those around them. Such change is slow but solid. Professor Yeh recalled his days studying abroad, deeply impressed by Japan’s local education: after children personally walk through and touch local shrines and other old buildings, they establish deep bonds with the land. Meanwhile, Japan’s numerous century-old craft brands and construction companies have made the restoration of old houses an integral part of everyday life, requiring no deliberate promotion, naturally attracting professionals from diverse fields.

As a preserver of Taiwan’s cultural heritage painted murals, Conservator Li Chih-shang reflected on his professional development journey, noting that the craft courses he took from undergraduate to graduate school mostly only introduced students to traditional skills, with a significant gap when it came to actual application. Joint consideration from both public and private sectors is still necessary to connect academically trained professionals with the industry. Li Chih-shang’s internship experience in Germany also influenced his concepts regarding the restoration of cultural heritage: if restoration processes are open to visitors, cultural assets can create cultural and economic benefits during the lengthy restoration period, allowing the public to get close to the craftsmanship involved, and thereby inspiring concern for historical spaces and traditional skills.

In the regeneration process of Lukang’s Chang-Yuan Hospital, Li Chih-shang’s Ming Hsiang Cultural team was responsible for the restoration of painted murals. During the restoration period, X-Basic Planning invited the public to visit the site and even collaborated with the team to organize workshops offering mural restoration experience courses. As Conservator Li Chih-shang observed, “After understanding the cultural value of their hometown, people develop curiosity and become willing to revisit the stories that once happened on this land.” Only when the public has opportunities to personally engage with and learn about traditional architecture can the vitality of craftsmanship truly continue.