Architectural painting: conservation and rebirth:

3/14 ꜰʀɪ. notes from Professor Li Chang-wei’s internal training

X-Basic Planning was privileged to host Professor Li Chang-wei (Taiwan University of Arts) for an internal training at our Taichung office. His lecture, “Practical Approaches and Philosophies in Architectural Painting Restoration,” provided a deeply insightful blend of academic and cultural perspectives. Professor Li, whose credentials include work on Japan’s Yakushiji Temple and Nikko Toshogu Shrine, not only provided a deep analysis of the historical and technical aspects of local painting conservation but also, through his international perspective, framed a critical discussion on the ethics and essential values of the field.

Pilgrimage and Legacy in East Asian Heritage

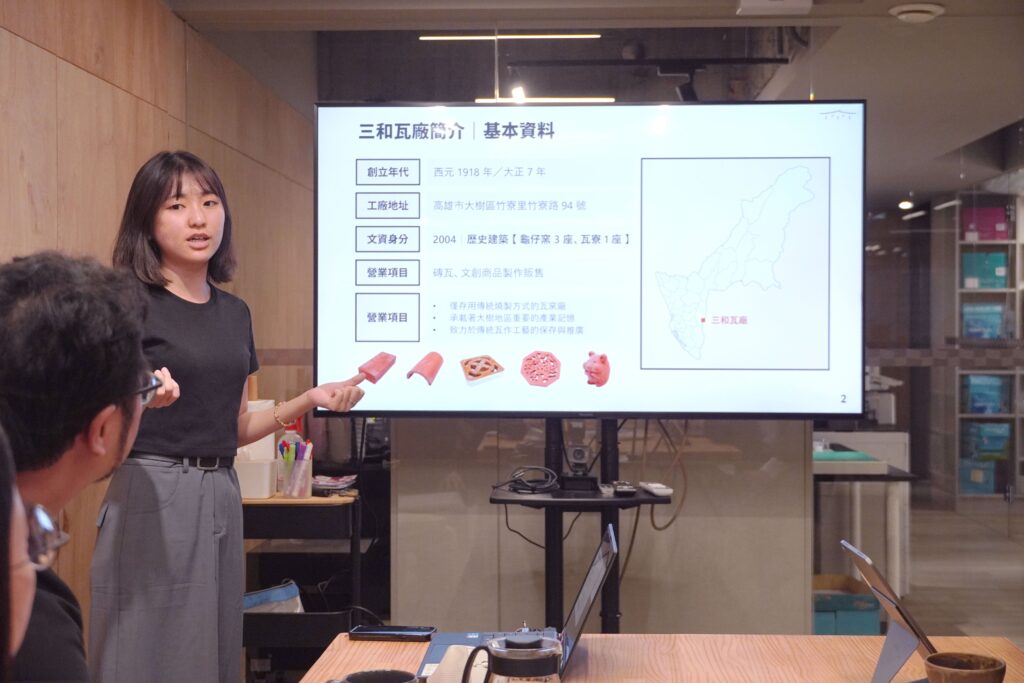

The lecture began with X-Basic Planning colleagues sharing two local examples of regenerative spirit: “SAN-HE Tile Factory,” which showcases innovative uses of traditional materials, and “Chang-Yuan Hospital,” which illustrates the diverse possibilities for old houses as cultural vessels. Following the local case study, the speaker transitioned to a chronological review of his many years of firsthand research on East Asian cultural heritage.

During his studies in Japan, Professor Li conducted extensive fieldwork, traveling by motorcycle to document more than 400 Ōbaku sect buildings across the country, an effort that informed his doctoral dissertation on Tang-style gable structures. Following his work on the painting conservation of Taiwan’s ‘Changhua Yuan Qing Temple,’ his focus returned to the international stage at Yakushiji East Pagoda in Nara—a project that realized his early passion for restoring ancient structures.

Recalling the Yakushiji East Pagoda restoration, Professor Li noted it was an interdisciplinary achievement, uniting experts in architectural history, archaeology, and art history, rather than the work of any single team or individual. The restoration team determined the structure’s condition and restoration history by referencing the West Pagoda, measuring its wooden components, and minutely examining every nail to trace its restorative path since the Nara period.

Beyond hands-on restoration work, building survey research has been equally critical to Professor Li’s development of a cross-cultural perspective. Through fieldwork spanning from Vienna’s World Museum to Japan’s Nikko Toshogu and China’s Yongle Palace, and through detailed surveys of archival materials in the British Museum, the Louvre, and the Pennsylvania Museum of Art, he has developed a macro-perspective for systematizing the technical, decorative, and cultural affinities and distinctions in international architectural heritage.

Of all his research cases, the World Heritage Site ‘Nikko Toshogu’ stands out as the most memorable for him. This complex, famous for its extreme opulence, actually triggered a nine-year ethical debate on its restoration in the early 1900s. Defying the contemporary Japanese preference for “preserving the current state,” conservation supervisor Shintaro Oe opted to repaint Toshogu Shrine traditionally. He justified this by pointing to its historical 20-30 year repainting cycle, arguing that its decay was a sign of post-Meiji poverty, not age. For him, restoration was an act of historical reverence. The decision sparked heated debate. Some urged preserving the status quo, while others favored an artificially aged look to retain the building’s antique charm.

The controversy at Nikko Toshogu—pitting the preservation of historical texture against a complete repainting—showcased diverse preservation perspectives and proved that restoration is not merely technical but deeply rooted in how we interpret history.

Beyond Mortise and Tenon: The Art of Making

Returning to a local context, Professor Li delved into the restoration of ‘Changhua Yuan Qing Temple’ to illustrate the methods and features of Taiwan’s painting conservation techniques. The most compelling part of the restoration was the “on-site competition,” a unique model that pitted master craftsmen from different schools against each other. Despite the rivalry, their work had to be chromatically unified, showcasing the delicate balance of competition and cooperation inherent to the craft.

The painting restoration of Yuan-Ching Temple featured two artisan schools: the Changhua Chen Ying School on the front hall and the Tainan Tsao Hsian-wen School on the main hall, creating a compelling north-south stylistic dialogue. The analysis then compared the two schools’ technical and stylistic approaches, breaking down their methods for the ground, ink drawing, and pigment layers.

Their ground layer techniques differed significantly: the Changhua school used breathable but labor-intensive pig blood soil, while the Tainan school chose tung oil putty for its full, warm finish. In their ink works, a clear contrast emerged: meticulous precision from one, and expressive freedom from the other. In pigment selection, both schools started with natural minerals but diverged in application. The Changhua school used classic “major colors” for an elegant feel, while the Tainan school employed a broader, brighter palette. Ultimately, both prioritized the temple’s overall harmony over rigid adherence to their preferred styles. As shown at Changhua Yuan Qing Temple, painting conservation transcends craftsmanship, embodying deep cultural significance and the soul of its masters.

“Each conservation of Eastern architecture’s elaborate paintings is an act of cultural transmission, ensuring the survival of an intangible craft.” Professor Li Chang-wei concluded by reiterating that the conservation goal extends beyond preserving a snapshot in time. It is about sustaining a building’s long-term life cycle returning to the original place/approach, thereby ensuring the transmission of craftsmanship itself.

From Yuan Qing Temple’s competitive craftsmanship to Nikko Toshogu’s preservation debates, Professor Li Chang-wei—through his profound scholarship and cross-cultural lens—elucidated the multifaceted nature of cultural heritage restoration: a complex interplay of technical skill, cultural values, and ongoing dialogue between tradition and modernity. The speaker emphasized that conservation is an ongoing endeavor, not a one-time project. Its true meaning can only be honored by deeply appreciating the intangible cultural and historical values, traditional craftsmanship, and period aesthetics.

This lecture inspires us to adopt Professor Li’s visionary, ethical, and cross-era approach to restoration practice. By steadfastly pursuing excellence, we are committed to forging a more sustainable future for Taiwan’s cultural heritage.